It goes to show us how quickly things can change. A little less than 2 years ago, Reid Hoffmann published his book ‘Blitzscaling’. While his thesis is actually much more nuanced and focused on the management aspects of rapidly scaling business models, the term blitz-scaling has come to be loosely associated with some of the more excessive examples of ‘VC deficit spending’ we’ve seen amongst startups. The thinking among many venture capitalists became that ‘massively scalable’ business models, often heavily reliant on the efficiencies and network effects of cloud infrastructure, and fueled by sheer limitless amounts of venture capital money would go on to ‘disrupt’ industry after industry. While this is, of course, true in part, some seemed to be thinking that every company can be blitz-scaled if only there’s enough VC funding behind it.

Enter COVID-19. While there is currently a lot of talk amongst VCs, which naturally self-select for diehard optimists, that the current worldwide pandemic is likely to fast-forward technology – and cloud adoption by a few years, I’ve observed another phenomenon. Good old fashioned ideas like ‘cost-saving’, ‘governance’ and ‘social responsibility’ and even, dare I say it, ‘profits’ are back en vogue. What happened? Money is still cheap and plentiful in startup land, despite record unemployment levels, which grew so rapidly that we’re struggling to find historical precedents. The US is back in depression-era territory, while the sheer explosion in unemployment over such a short period of time might well be a first in the history of the country.

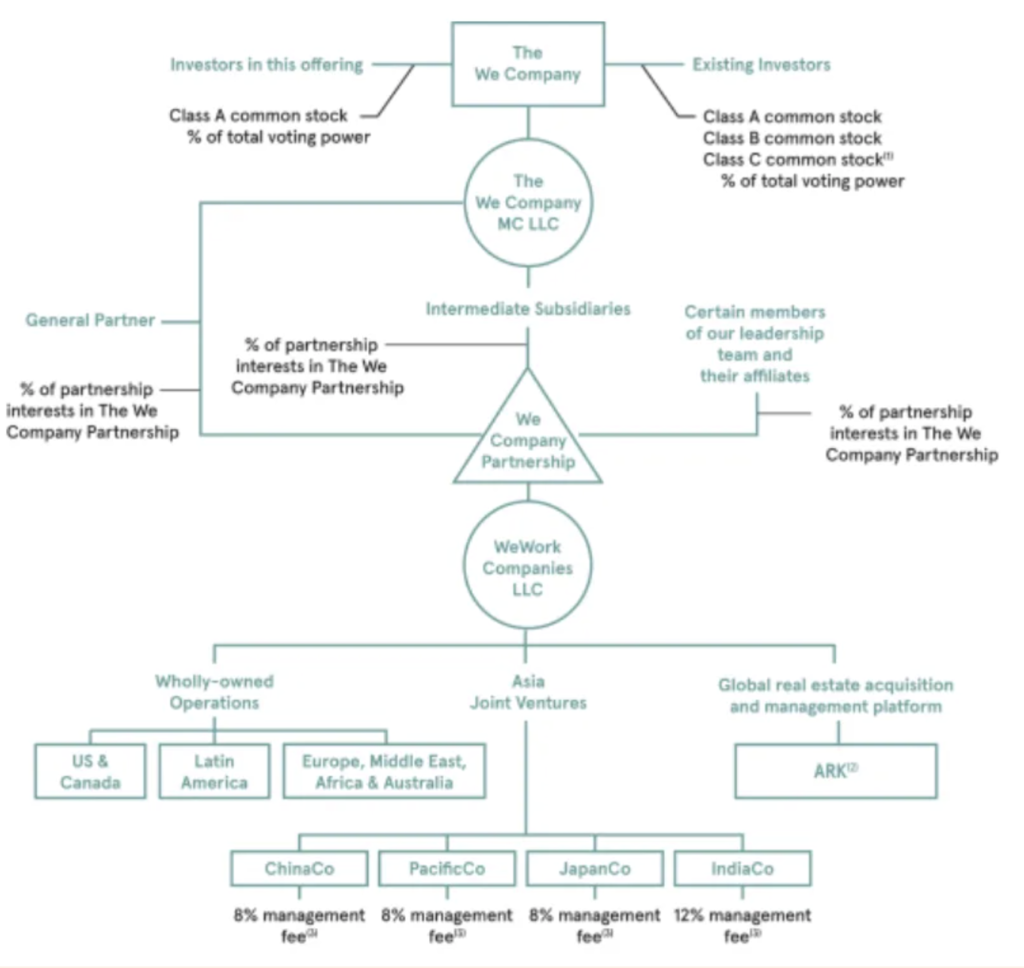

Many conversations with founders these days are led by discussions around cutting salaries across the board by 10-30%. Often senior management is taking a much steeper cut citing moral leadership and social responsibility, words which were famously absent from WeWork’s S-1 filing. The fallout from which has been palpable: Attempted explanations of ‘Community Adjusted EBITDA’ (a.k.a. spending $2 for every $1 you make) have given way to clear projections of profitability. Mission statements such as ‘Elevating the world’s consciousness’ seem to no longer be enough to attract Vision Fund type funding. Describing that a founder is a ‘unique leader’ while simultaneously disclosing that said company has “entered into a number of transactions with [said] Founder […] including leases […] in which [they have] or had a significant ownership interest” is probably a thing of that past for now. That’s a good thing.

A recent example of changed attitudes is a company called Omneky where I’m also an investor. As a successful serial entrepreneur with top credentials, its founder and CEO Hikari Senju got approached by VCs before even thinking about raising money but has mostly declined offers to invest. The company focuses on creating AI-generated personalized ads at scale and has stayed unusually frugal, generating revenue and turning profitable within several months of its founding. While Hikari has taken on some top investors like The Village, his reluctance to take excessive venture funding early on while bootstrapping as far as possible stands in stark contrast to the WeWorks of this world, which raised ‘fuel growth’ to ‘blitz-scale’.

Especially in early-stage companies, the pendulum is swinging back towards more conservative financial management. Of course, we have to look at this trend against a wider macroeconomic backdrop. Ultra-low interest rates, resulting from massive central bank intervention since the 2008 financial crisis, have taken their toll and completely skewed the picture when it comes to raising capital. As Hikari recently put it, companies generally have two objectives, which are to grow and to make profits. In a world of negative-yielding government bonds, there’s significantly less pressure on companies to generate profits as they no longer have to pay dividends to compete against the yield on debt. Hence companies compete for growth and capital will accumulate at any company with high growth.

Pension funds are, of course, the world’s largest Ponzi scheme if it weren’t for people dying, which venture capitalists like Peter Thiel are enthusiastically working on ‘solving’.

Central bank actions have therefore made it easier than ever for a tech company, either with high growth or with the promise of high growth, to raise capital. Another way of looking at Hikari’s argument is realizing that most investors need to achieve a certain yield to keep the lights on, especially pension funds, endowments and sovereign wealth funds. All of which are required to deliver a fixed annual payout to their creditors (pensioners, institutions and governments, respectively). Pension funds are, of course, the world’s largest Ponzi scheme if it weren’t for people dying, which venture capitalists like Peter Thiel are enthusiastically working on ‘solving’. In order to be able to pay out the fixed 8% or so a year to pensioners, pension funds are now forced to invest in ever riskier assets. Stocks and bonds will no longer do it, which is why VCs have embraced pension funds as their new best friends to raise record size funds. VC is the new PE [, baby!].

After investors piled over $3 billion into Magic Leap over 5 years, which hired over 2,000 people, the company recently had to let go of 50% of their employees according to layoffs.fyi, a site which tracks recent layoffs at startups. So while VC money is more plentiful than ever before, founders are, by contrast, rediscovering long-forgotten virtues like moral leadership, social responsibility and frugality as a more sustainable path than the one chosen in days past. Of course, Reid Hoffmann is right that our cloud infrastructure and business models built off of it can scale at dizzying speed, which requires a rethink of management not seen since Peter Drucker. His book also points to the right way of doing so for the right kinds of businesses. Some of the misconceptions around blitz-scaling, however, are now laid bare in the current crisis. Money to expand and make those necessary growth investments along the way is readily available but should be taken on at the right time.

In a way, the current overall gloomy picture might actually give way to a new golden age of venture capital as human ingenuity will overcome most obstacles and we’ve learned from our mistakes. After Corona, climate change is already lurking around the corner as the next global challenge. For these problems, we need blitz-scaling more than ever but we have become smarter to avoid blitz-failing. This makes Reid Hoffman’s book very current. Meanwhile, Hikari is contemplating raising some external growth capital after closing a healthy, profitable year 2, while having retained the vast majority of equity in his business.