First a chart…

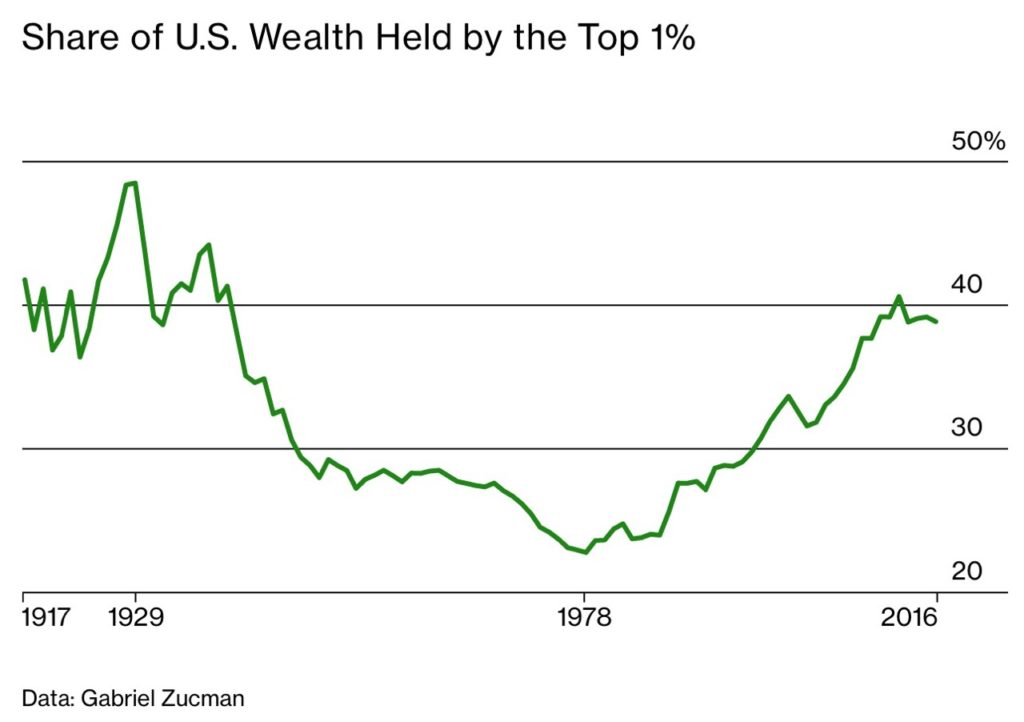

The chart above recently sparked a debate in my family. What does rising wealth inequality mean for millennials’ expectations to continue living in a peaceful, open society? Is the U.S. now really similar to the time of The Great Gatsby when it comes to the “wealth gap”? Or is this chart misleading because it doesn’t say anything about overall living standards and physical or mental well-being? Or if it does, in fact, suggest that inequality has risen dramatically – should this at all be worrying? Let’s explore the underlying drivers that lead us to this point. How has inequality developed historically and what might be done to bring us on a more sustainable path?

The drivers of modern inequality

There is a lot to unpack here and while history is often a good guide we’re pretty much on uncharted territory. One could argue that the current mega-trends we’re experiencing are entirely driven by technology and our use of resources. Connectivity (of people, goods, and information), automation and climate change are such drivers. Connectivity, in broad terms, can be split up into two more effects. First, globalisation, the interdependent supply- and information chains affecting politics, business and societies. Second, the monopolisation of information. Central nodes in networks benefit exponentially more from the free flow of information, which leads to natural monopolies.

Globalisation describes the co-dependencies that are built up by more “connectivity” in the broadest sense. For example, economies of the past were largely shielded from one another by relying heavily on domestic consumption. Now, the U.S. cannot start a trade war with China without inflicting heavy damage on its own economy. If China were to retaliate by fire-selling U.S. government bonds that it has piled up over the last decades via its current account surplus (it is now the second-largest foreign creditor of American sovereign debt), it could possibly ruin the U.S. economy all-together, although not without drowning itself along with it.

Globalisation goes beyond connected economies, however. Through Netflix, the whole world is now streaming international media content to their living rooms. Cheap air-travel means that people themselves are more mobile than ever before. These days you can sit at Starbucks in Beijing with people from all over the world. You’re also more likely to hear English around trendy coffee shops in Berlin than German. According to a recent article in the Economist, Mount Everest is now getting so busy that you have to queue up to climb it. Apparently, everyone wants to take that perfect selfie for their Instagram account. Soon, you’ll have to exit through a gift shop.

All of these are by and large good things if you, like me, believe that trade and any voluntary exchange for that matter benefit both sides. This can be cultural, economic or just social. Sadly, this view has almost become controversial in recent years. There are various factions on the far right (“alt-right” in the U.S. and plain old neo-Nazi in many parts of Europe) who believe that there’s some conspiracy underway to ‘replace them’ or ‘create multicultural societies’. I hate to break it to them but there is no conspiracy. The only way to avoid this trend would be to take away your internet, passport, and car. And avocado toast. And Amazon Prime. If that’s not what they want they’ll have to get used to greeting their various new neighbours in different languages. It’s actually great news because they’ve already been watching Netflix shows from their native countries. It’s nice to finally get to know them and say Ni Hao, Bom Dia or just simply Welcome!

Returning back on topic, the building of international networks has also brought on the information age or ‘post-information age’. Whatever is meant by that. It also led to information monopolies. As Jaron Lanier pointed out in his book “Who Owns the Future”, giant networks reward those nodes (or actors) with the most links. In the case of the internet, a.k.a. computer/ server networks, this ultimately leads to ‘siren servers’ as he called them. These are players on the network that are so large that it becomes impossible to fully use the benefits of the network without passing through them. Yes, you knew where this was heading. Enter Facebook, Google, Amazon and a couple more, including lesser-known financial services companies and, naturally, also governments.

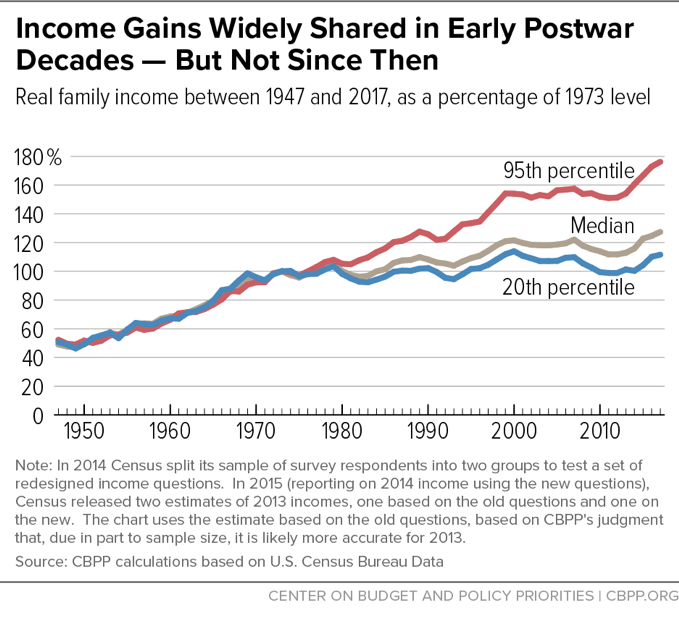

Now, how do globalisation and information monopolies lead to inequality? While both have arguably produced incredible wealth overall, the proceeds have been much less evenly distributed. Globalisation has allowed people to study all over the world but also increased competitiveness to unprecedented levels.

If you’re a business in the U.S. that can’t compete with cheaper manufacturing in China, you’re out. Likewise, on the job market: If you can’t compete against the brightest minds from all over the world: You’re out. While median wages in the West largely stagnated over the last 20 years, college tuitions have risen by around 200-300%. If you can’t compete and you’re not provided with a leg up by wealthy, connected parents, you’re simply priced out of the ‘American Dream’. At least, compared to a generation ago.

Similarly, information monopolies manage to extract vast amounts of data through their ‘siren server’ position, which they then monetise at often breathtaking levels of profitability. The proceeds are subsequently spread amongst a comparatively small cohort of employees and shareholders, while mostly excluding others in the ‘value chain’. Most often there are only very limited staff and/ or suppliers, for

Inequality Then and Now

We’ve seen global monopolies before, in the form of the East India Company in the 18th century and Standard Oil in the early 20th, for example. What’s different this time around is that internet giants can leverage technology to achieve scale and market-dominating positions with unprecedented efficiency. There’s a limit to how fast you can lay railroad tracks but not how much data you can collect, process and

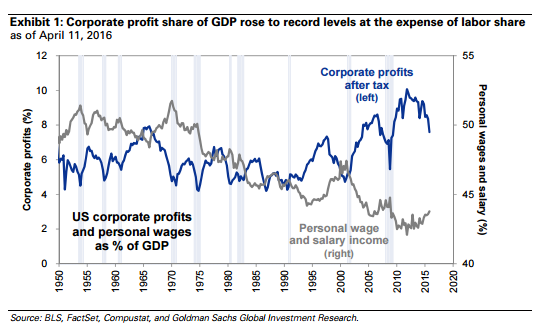

What does this have to do with wealth inequality? While the railroad or even the oil monopolies still had to employ vast numbers of people to run their operations and expand their business, digital monopolies are ‘scalable’, meaning you can have the same number of people running more or less the same servers but process 10x or 100x the amount of data while growing the business accordingly. This means you can run a large digital business with a fraction of the employee headcount. At a time of record corporate profits (exacerbated by record-low corporate taxes), this means rising profits are shared by fewer people. The chart below doesn’t even include the 2018 Trump tax cuts for corporations, which caused profits to soar to unprecedented levels.

You might argue that rising corporate profits will ultimately ‘trickle down’ and pay higher stock returns to pension funds and everyone with a stock portfolio, which is… everyone, right? Well, first off, according to the Washington Post (I know, the ‘Amazon Post’), less than half – 46 per cent – of the US population actually hold any stocks at all. What is more though, is that corporate profits are increasingly distributed in private, not public companies. Witness the incredible shrinking stock market. You might think that with all things bubbling and growing, the stock market would too, in size. It hasn’t. Between 2000 and 2018, the number of publicly listed companies actually fell from 7,000 to about 4,000. During the same period, the number of private equity-backed companies in America rose from less than 2,000 to nearly 8,000. (via the Financial Times).

The shrinking of public markets means that there are fewer and fewer opportunities for the average person to participate in the country’s wealth creation, further exacerbating the problem of wealth concentration. Stricter regulation of the public markets, especially since the 2008 financial crisis, had the side-effect of pushing more capital into the private markets and, ironically, out of the reach of ordinary tax-payers who were after all footing the bill for the said blow-up. Not only that but, in the U.S., private debt markets have grown to over $600bn according to data by the Financial Times. Given that these markets are far less regulated, there are mounting concerns over their systemic risk posed to the wider financial system. Even though they are theoretically contained by only involving private creditors (by definition), they still ultimately involve large counter-parties (keyword “shadow banking”) that could bring down parts of our financial system and force a public money bail

That’s a pretty bleak thought and will probably, I suspect, be a hard sell to the austerity-fatigued public. With both wealth and income inequality in advanced economies at peak levels since WWII, we have to begin asking ourselves if this path is sustainable. The immediate answer if of course a resounding no but as ever, it’s important not to jump to immediate conclusions with an issue as complex as this socioeconomic one. I think we have to start asking some basic questions about our current system, the outcomes we actually want to achieve and how we can adjust our machine to deliver better results for everyone.

Could it be possible that with rates of extreme poverty at all-time lows and even for those whose incomes have stagnated receiving more services at a lower cost or for free by technology companies we actually shouldn’t worry about overall inequality? If everyone has their basic needs met, does it matter if there is an increasingly concentrated, hyper-wealthy elite? In discussing this with family and friends, I heard diverging views.

It is reasonable to ask if rising inequality is indeed unsustainable or even a bad thing. As long as everyone’s needs are met and other measures of ‘happiness’ or ‘material wealth’ are increasing for everyone maybe that’s just good enough? After all, if your gadgets are upgraded every year and you get fantastic (often free, too) new services every year curtesy of Google & Co. why should you care that your personal data is ultimately enriching a Silicon Valley elite earning 1’000-10’000x your annual salary? Fair enough. Taken to an extreme, however, there are problems with this, which I will elaborate on later.

Is greed good?

This year’s Milken Institute Conference in May produced headlines like “Even billionaires are acknowledging that the system that created their crazy amount of wealth is unsustainable“. The conference has come a long way since its start in the 80s when Micheal Milken started what quickly became known as the ‘Predator’s Ball’. Back then it focused on yield-hungry investors’ discussions around junk bonds, which made Milken a fortune. The conference’s early spirit was made famous by Oliver Stone’s film “Wall Street”, in which corporate raider Gordon Gekko said, “

“Even billionaires are acknowledging that the system that created their crazy amount of wealth is unsustainable.”

Headline – Business Insider, May 6, 2019

From Gordon Gekko’s point of view, he is simply operating in and praising a system that we have all more or less agreed on to run our society. The big problem stems from the fact that everyone knows that this system has flaws. Western societies have essentially agreed that capitalism, democracy and some degree of socialism is the worst system except for all the others that we’ve tried. This system has worked remarkably well over the past centuries, turning animal spirits into productivity, innovation, and growth but it needs constant refinement.

The long view

That fact that income inequality would become a significant problem down the road (now) is actually not very surprising. After the last great ‘equalisers’, the disaster of two world wars, we found ourselves in such an unprecedented period of growth for all income groups that there wasn’t too much concern around the distant future in which inequality would finally cause a disruption but the truth is that the only thing that had slashed inequality reliably throughout human history was catastrophe.

We have to understand that inequality is as old as civilisation itself and that, barring rare exceptions, only devastating events such as revolution, war, famine or disease (e.g. the Black Death) have brought it down dramatically. Interestingly, it is often peak levels of inequality that can become a catalyst for upheavals in the first place (e.g. the French Revolution). Of course, this doesn’t mean that we should resign our future to the boom and bust cycles of days past. The rise of socialism and the modern welfare state were precisely developed to alleviate this tragic flaw. Alas, the past few decades have shown that it is not enough.

Some bright spots exist in modern times: Brazil brought inequality down by 20% in the early 2000s through social reforms that lifted tens of millions out of poverty and educated broad swathes of the country with the Bolsa Família program. This was, however, in one of the most unequal countries on earth and speaks more to the fact that we have effective policy tools to reduce inequality to some degree without hurting overall productivity and innovation. For advanced economies, even those with high levels of redistribution such as the Nordic countries, growing wealth inequality remains an unsolved problem.

So, what (can be done)?

Usually, high levels of real (or in some cases even perceived) inequality are fertile ground for the rise of populist leaders and political disruptions, which may or may not end badly. To some extent, this is rational behaviour. The longer you’re playing a game in which you’re losing, the likelier you are to try some radical new strategy (populism, fascism/ communism were flavours of this in the past) or simply turn over the board (revolution/ anarchism). Putting this all together, the billionaires at the Milken Institute Conference are right to be concerned. As calls for their (so far metaphorical) heads are growing louder, they are beginning to have a self-interest in fighting inequality.

But how? In theory, the state could just redistribute everything – take from the rich and give to the poor. Well, of course, our billionaire friends are right that this would crush innovation and ultimately make society as a whole poorer. British prime minister Margaret Thatcher famously accused her Labour Party rivals of that “they would rather that the poor be poorer than the rich be richer”. She has a point. So what we’re looking for is an equilibrium. Technology has changed the underlying principles of how the world works and our current systems of redistribution no longer seem to be working. In short, we need to have a fundamental debate around taxation.

The world’s tax codes are horribly antiquated, subsidising ailing industries, ignoring social costs of contributors to climate change, for instance, and not being able to capture revenues from multinational businesses. Internet businesses such as Google, have amassed some of the world’s largest profits in history and yet are paying obscenely low effective tax rates and in many cases none at all to countries where significant revenues are generated.

A recent French proposal to tax Google for profits that can be traced back to its operations in the country seem perfectly reasonable and the ensuing debate highlights the absurdity of practices that shift corporate revenue/ profit streams between countries to minimise taxation. Of course, the taxation of individuals is also a hotly debated topic around the world after globalisation has also allowed for tax evasion on an unprecedented scale. Thankfully, the world has already taken significant steps to act on this issue, which is why I will continue to focus on corporations.

There are however a number of tools on the individual tax shelf that should be considered:

- Tax wealth

As simple as that. Wealth is actually a much more reasonable thing to tax than even income. People will still want to build up significant wealth but there is a tax for holding sway over significant resources. Switzerland has it – it works well. - Global income tax harmonisation

This has already happened to some extent. Governments need to work together to sign more double tax treaties and make it less difficult for the increasing number of individuals who live, work and travel across multiple jurisdictions.

As the world has already made substantial progress on individual tax reforms, let’s focus on corporate taxes. The system is fundamentally broken and it’s not (fully) the fault of companies. Other than their numerous positive contributions to society businesses can have tangible costs for it, too. The corporation as a legal concept is probably one of the best human inventions of all times but in our current system all costs for society must be accounted for through essential (though not excessive) taxation and regulation.

What are common burdens on society that businesses can produce, which should be discouraged systematically:

- Consumption of scarce resources

Water, electricity and any other increasingly scarce commodities are already taxed in some countries but are even subsidised in others. - Pollution of the environment/ contribution to global warming

A global CO2 tax is increasingly inevitable, as well as, naturally, regulation through setting environmental standards. - Increase in income inequality

- Introduce global taxation schemes, especially for digital businesses. Develop mechanisms to trace revenue and profits to the

country of origin for appropriate levels of taxation - Introduce tax-breaks for public companies to encourage transparency and broader participation in growth.

- Regulate and in some cases break up digital businesses where monopolies suppress competition and information monopolies leads to ‘siren servers’.

- Introduce global taxation schemes, especially for digital businesses. Develop mechanisms to trace revenue and profits to the

In summary, if history and recent decades are any guides, we’re on a path of continuously rising income and wealth inequality. This is accelerated by technological advances with resulting trends of connectivity, automation and climate change. Now, let us make the reasonable assumption that rising inequality will eventually be unacceptable to society and thus make at least democracies unstable. This would mean we’re headed on a collision course and there seem to be historic precedents to back this up. The most effective tool to counter this has already been invented: redistribution through taxation.

We need to double down on the approaches listed above to make growth sustainable and keep societies stable. It might not solve the problem of rising inequality in the long run but it can significantly delay a breaking point. Countries that already focus on a holistic approach to counter inequality to a greater extent (such as certain northern European countries) have managed to contain the problem far better. The good/ bad news is that inequality and climate change are linked and that we can combat both with the same policy tools. It would be a moral failing not to do so in time.