Johann Sebastian Bach is NOT overrated. While it’s difficult to pick favourites among the greatest composers of classical music, when pressed, I just love Bach a little bit more than the other great musical geniuses and admitted as much in an earlier book review. In a slightly morbid thought-experiment, I sometimes find solace in the idea that if I were ever physically trapped in some desperate situation I could still find pleasure in playing Bach’s music in my head over and over again. An important part of this ‘playlist’ would be Bach’s famed Cello Suites (Six Suites for Unaccompanied Cello, BWV 1007-1012).

Having listened to these 6 pieces countless times, I’ve had the chance to compare different recordings by different performers against each other and it was a unique experience to hear Yo-Yo Ma perform the full 6 suites on December 6th at the Maison Symphonique de Montréal. Because the concert hall and second overflow hall to which the performance was televised were completely sold out almost a year in advance, the directors of the Bach Festival decided to make additional seating available directly on stage where a lucky few, myself included, were able to sit in intimate proximity to the performer. It was a really special experience. Yo-Yo Ma, in his typically warm and kind fashion, went out into the cold to enter the overflow hall first and greet all his listeners in person before returning to us to start his performance.

Before going into the details of this evening, however, let me go into the Cello Suites more broadly and discuss a few different interpretations. First and arguably most famous are the recordings by Pablo Casals. Pau Casals i Defilló was born in Catalonia, Spain, and first discovered by the Spanish composer Isaac Albéniz in 1983 while performing at a café. Through various introductions and references, Casals quickly began touring across Europe and beyond, performing for the likes of Queen Victoria in 1899 and Theodore Roosevelt in 1904, building one of the biggest names in classical music for himself. Below is a photo of the by then world famous Pablo Casals together with Fritz Kreisler and other grandees of the classical music scene at the time around a concert at Carnegie Hall.

Casals plays the Cello Suites with an incredible warmth but also technical excellence, always in tempo and beautifully balanced. His recordings are subtle and emotive. His sound is also associated with his political stance at the time. Casals was a strong supporter of the Spanish Republican government and after its defeat in the Spanish Civil War in 1936, declared not to return to Spain until democracy was restored. Going further than this, he wouldn’t even perform in countries that recognised the Francoist state, although he did make some exceptions to this rule such as to perform at the White House by invitation of JFK and later on to pick up his Presidential Medal of Freedom (can we blame him?). Sadly, he died aged 96, just 2 years before the end of the Franco. What remains are some of the most beautiful Bach recordings ever made. That and also the Puerto Rico Symphony Orchestra, which he founded.

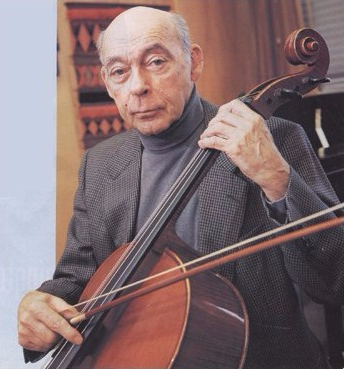

Next up as a contender for the best Cello Suite performer of all times is János Starker. Starker grew up in Budapest, born to Jewish parents of Russian and Polish descent and survived the second world war in his hometown. His two violinist elder brothers did not – they never returned after the family was sent to to a concentration camp for 3 months. When János and his parents were released, he worked his way to Paris as an electrician and a sulfur miner, while also releasing his first recording that same year. Since he was never granted Hungarian citizenship, he spent the post-war years in visa-limbo, while still giving successful concerts in Vienna and Geneva. After moving to the United States, he later settled in Bloomington, Indiana and became a professor at the Jacobs School of Music.

By this time, 1958, he was already famous in classical music circles and went on to produce over 150 recordings, winning Grammy awards and nominations in the process. He was active until his death, aged 88, despite his regimen of smoking 60 cigarettes per day. Below, you can watch the great man himself at age 76. His playing is enunciated but not slow, sophisticated and yet elegantly effortless.

After this brief stroll down Bach memory lane, we’re finally turning back to our contemporary Yo-Yo Ma and his performance in Canada. Yo-Yo Ma is coming on stage. Nothing but him and his Montagnana cello from 1733. As he sits down the lights are dimming and the audience goes completely silent. Everyone is waiting for the famous first notes of the Prélude to Bach’s Cello Suite No. 1 in G major. And it begins. Yo-Yo Ma’s style of playing is masterful, effortless. Comparing it to Starker, he may be interpreting Bach’s music a little bit more lyrically, ever so slightly more emotional, closer to Casal’s interpretation.

His warm, likable, character comes to shine again when after the first suite (and in between the others), he stands up and encourages the audience to do the same, animating us to do a few jumping jacks. He knows that sitting through all of the Cello Suites is a long, demanding program for the audience. In typical Yo-Yo Ma humbleness, he is also completely deflecting from how demanding it must be for him. After all, he is playing around 3 hours of music as a soloist completely from memory, with every note listened to and carefully judged and weighed by the audience. He remained as enthusiastic throughout and after thundering applause following the 6th suite, took to the microphone to exclaim jokingly in fluent French (he was born in Paris) that they have discovered the 7th suite recently so we should settle back in…

Just weeks before this concert, Yo-Yo Ma gave a special performance for all major political world leaders and presidents on November 11th 2018 in Paris to commemorate the WWI Armistice. At a time where the world’s political future seems to grow more uncertain, here, music and Yo-Yo Ma in particular showed a special ability to unite people in praise for the arts. Always open to new ideas and willing to experiment, he used his talents again this evening, inviting a young aboriginal Canadian musician on stage for his encore. Together they improvised and played traditional melodies with a range of instruments and singing, always accompanied thoughtfully by Yo-Yo Ma’s cello. When the audience broke out in applause once more, he stood aside pointing to the young musician he had invited, smiling widely not because of the recognition he, Yo-Yo Ma, is receiving but because of the joy he brought to everyone else in the hall and beyond. Befitting for Bach’s music, Yo-Yo Ma is class act and a true mensch.