This book was not a serendipitous purchase. I have always liked biographies for several reasons. Many argue that life still produces the most interesting stories – often more empathetically engaging and visceral than anything an author could dream up. What makes them my favourite literary genre, however, is something else. Well-written biographies capture not only the protagonist’s life but also everything surrounding them, often giving apt descriptions of points in history, places and much more. A good biography doesn’t only teach youabout the person but about history and society in a much wider sense. In this context, biographies of well-travelled, -connected and in all likelihood older figures are all the more interesting.Very few people have in their lives extended those three horizons as far as Moses Montefiore who’s life spanned from 1784 to 1885.

As someone who reached the at the time sheer implausible age of 100, he also had the resources and will to fill his long life with numerous adventures – travelling across the globe in his lifelong pursuit to help the needy. After retiring as a banker at the end of the first half of his life, he dedicated the rest of it to help where he was needed by replying to sometimes dozens of individual, written requests per day as well as watching over political events in Europe, negotiating with rulers to secure the rights of minorities whenever it was needed. It was this dedication to the betterment of humanity that made him world-famous, with his 90th and later 100th birthday (in itself an unusual event at the time) being celebrated in newspapers across the world. Sir Montefiore was born on a business journey in Italy in 1784 to a wealthy English family of Italian Jewish descent. His brother-in-law would later be a successful London banker from the prominent Rothschild family with whom Montefiore partnered and became a very successful financier in his own right. His position as one of the wealthiest man in the world and the great misfortune of his life to not have had children resulted in his intellectual and emotional decision to use all resources available to him to help others. He thereby single-handedly invented modern-day philanthropy. Almost 150 years before Bill Gates and Warren Buffet would sign their famed Giving Pledge, Sir Moses made a conscious decision to give away all of his money, across the cultural and political divide while developing plans of how his investments, as he saw them, can have the maximum effect to help humanity. He was what we would nowadays rather more pompously call an impact investor. On his numerous trips to Damascus, Alexandria, Jerusalem, St. Petersburg and many other cities, he always listened to the problems of the poorest who would hear about his arrival weeks before and await him with eager anticipation. Montefiore was always particularly concerned about the problems of Jewish communities but consistently made sure that he donated money to causes of all people.

In 1839, the Damascus affair, a blood libel that accused the local Jewish community of having killed a Christian boy and thus threatened the community to be exiled in the best or slaughtered in the worst case, Montefiore was quick to use all his political channels to protect them. He was unequivocally supported by none other than Adolphe Crémieux, the famous French lawyer and James de Rothschild, the influential German-French banker. Referring to France’s pivotal role in granting equal rights to all her citizens, Crémieux’s appeal to his Christian fellow citizens was: “you have set the world an example of the gentlest and purest toleration. Serve as our shield having served as our support!”. As the Jews of Damascus were “beaten to such an extreme that their flesh hung in pieces upon then” and children at primary school were chained and incarcerated in the expectation “that the fathers for the sake of liberating their children would confess the truth of the matter”. Alarmed that such sentiment might go international as it has before, the alliance of French and English noblemen negotiated a solution with lukewarm support of their respective governments. Mehmed Ali, who controlled Damascus and had shown no interest of intervening previously, restored order and justice after formally agreeing to submit to the Sultan immediately and be rewarded with hereditary rule in Egypt and control of southern Syria for his lifetime, becoming the Viceroy of Egypt- a deal that required herculean efforts to be struck. Stories like these reveal a great deal about how international politics worked at the time. The detailed descriptions of Montefiore’s various journeys show how the Middle East has always been influenced significantly by European powers through a complex web of interests. The Damascus affair is just one example of many crisis that threatened the survival of a local minority. It is, on the other hand, surprising to read in many parts about a largely secular and tolerant Middle East with monarchies that protected its minorities – the litmus test for any civil society. This stands in stark contrast to today’s Middle East, which strikes me as much more radical in the sense that few countries of this part of the world favour the multi-sectarian landscape that has for so long shaped the region.

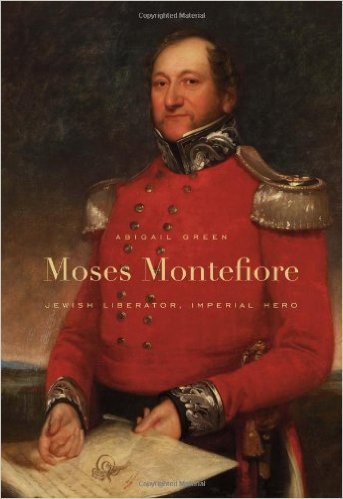

It helps to learn in the Preface that Abigail Green is related to Moses Montefiore, which gave her complete access to the family archives in addition to many other private and public collections. This comes to showin the work’s extensive, well-researched detail, making it without a doubt a very important account ofmodern European Jewish history as well as the political, business and philanthropic life of the day. On a more critical note, there is something that often happenswith biographies. I feel like whatgoes beyond the ambit of this book is to capture life’s serendipity, which is of course not something that can easily be researched into. Let me tell you what I mean by that. It is all too natural for humans to look for underlying reasons, which often leads to thearrival at illusional connections or even supposed causations that weren’t really there at the time but are merely the result retrospective construction. With such a towering figure as Montefiore and such central themes as charity, piety and political activism it seems even more temptingto argue that everything he did was part of the same life-long focus. While this may well have been the case, we all know from our own lives that many twist and turns are largely due to sheer coincidences and not years of planning, rendering some episodes in the booknot quite convincing in their detail or at least without too much concern for other factors that may have influenced his decision-making. Arguably, that would have bloated the length of this book further still. After reading Moses Montefiore – Jewish Liberator. Imperial Hero. one is left with the urging sense that when at a time where each journey across the mediterranean sea was still a dangerous undertaking, individual people made such a difference in the world, that there should be many more today using the tools available to our modern society to devote their resources to the betterment of humanity. People like Bill Gates, Warren Buffet and many others who signed up to the Giving Pledge or who fulfill a similar commitment today should look to the now largely forgotten figure of Sir Moses Montefiore, who showed that one life can serve to make a difference in the lives of tens of thousands.