Henry Kissinger is one of the architects of our current political order. First sworn in as fifty-sixth secretary of state on September 22, 1973, he received the Nobel Peace Prize that same year, the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1977 and the Medal of Liberty in 1986 and shaped US foreign policy and interventions over decades. This was a world away from Fürth, Germany, where he was born in 1938 as Heinz Alfred Kissinger to an orthodox Jewish school teacher. Looking back on his experience in foreign policy, he published one of his most important books Diplomacy in 1994, which opens with the first chapter The New World Order.

With the election of Donald Trump and rising nationalism across the world, it seems as though we are entering a new chapter – a new New World Order. As ever, it helps to understand the past to make predictions about the future, which is why I was looking forward to reading Dr. Kissinger’s new biography by Niall Ferguson. This is the first of two volumes and looks at his rise to a highly influential public intellectual – maybe the first of his kind.

As an author, Ferguson understands to not isolate his subject but show all the choices and limitations presented. In order to achieve this, Ferguson went through 111 archives worldwide and 37,645 pages of documents. In the Epilogue, he promises a Bildungsroman and cites Goethe: Every thing that happens to us leaves some trace behind it; every thing contributes imperceptibly to form us. By allowing historical facts to speak for themselves and limiting editorial notes, he mostly succeeds in fulfilling this promise.

While not trying to over-analyse Kissinger’s experiences as a child in Nazi Germany and later as an American G.I. in West Germany after the war, the book nonetheless highlights clearly how Kissinger’s early experiences contributed to his sense of purpose and political instincts. Sub-titled, The Idealist, Ferguson suggests that he was very much driven by a benevolent sense of bringing justice and freedom to the world.

Unlike my generation, having grown up in the West after the end of the Cold War in relative peace and amid political constants, Kissinger’s generation has seen political extremism and disarray – the falling apart of countries, both socially and politically. For some, this experience has turned people into radical pacifists, rejecting all forms of militarism and violence. For others the lesson has been that force may be absolutely vital to defend one’s moral values and liberties vis-a-vis an aggressor, following Realpolitik which is a term often associated with Kissinger.

Kissinger wrote that:

Whenever peace – conceived as the avoidance of war – has been the primary objective of a power or group of powers, the international system has been at the mercy of the most ruthless member of the international community. Whenever the international order has acknowledged that certain principles could not be compromised even for the sake of peace, stability based on an equilibrium of forces was at least conceivable.

This highlights his understanding of what the game of international power was about. Erudite in European history, Kissinger studied Bismarck extensively in his early books. According to him, Bismarck’s Europe was too democratic for conservatives, too authoritarian for liberals and too power-oriented for legitimists with the overall order having been tailored to a genius who proposed to restrain the contending forces, domestic and foreign, by manipulating their antagonism. Ironically, some critics may have found elements of this in his own style.

Kissinger is acutely aware that the world’s future is by no means inevitable and that it is simply the consequence of the decisions made by major actors. Giving a sense of this, I recently came across an animation of European borders over the past 2000 years. It is a good reminder of how politics is in constant flux and seemingly stable political entities can vanish into thin air within only a few years. The Holy Roman Empire was a constant over almost 1000 years – for any individual living in those days, it must surely have seemed like an eternal constant – until it, too, vanished.

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oWWLECJnylM&w=560&h=315]

Ferguson starts the book strictly biographically, which gives a good sense of Kissinger’s background and major influences. He grew up with his family in an orthodox Jewish community in Fürth, Bavaria but fled to Washington Heights in New York like thousands of other Jews when Hitler took power in Germany. The author describes how many refugees, including the young Kissinger, adjusted to their new environment. American Jews largely looked down on them as newcomers and nearly everyone in Washington Heights had a better life in pre-Hitler Germany than they found in their new existence.

A German-language paper at the time warned newcomers that in this country… there is no organized community. […] The authority over Jewish questions, including kashrut, is not established [and] […] Rabbis whose knowledge of the law qualifies them to be authorities may not be recognized by the community as such. Despite occasional antisemitism, even in New York, the fifteen-year old Heinz Kissinger was thrilled to walk the streets of the city without the fear of being beaten up from the moment his family’s ship docked at the Terminal on Manhattan’s West Side by ‘Hell’s Kitchen’.

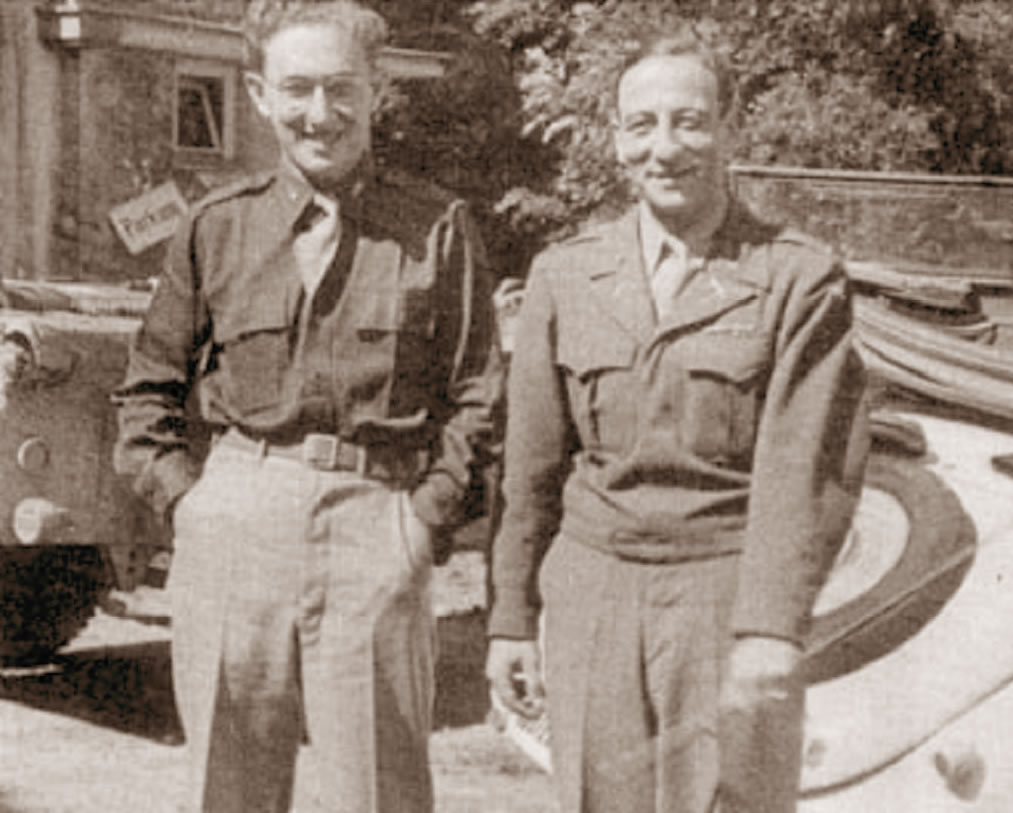

From his young adult life on, one of Kissinger’s strongest influencers became Dr. Fritz Kraemer. To one account, Fritz Kraemer was the most influential German in the Pentagon from 1952 to 1978 as Geostrategic Advisor to the U.S. Army Chief of Staff in the U.S. Department of Defense. The true “Dr. Strangelove” – complete with monocle and walking stick, a last Prussian on the Potomac River in Washington DC.

Like Kissinger, he was a German emigrant to the U.S., born in Essen in 1908, with a Christian denomination but Jewish roots. Having experienced the German Empire, the Weimar Republic as a student and later the rise of Adolf Hitler, Kraemer was strongly influenced by these experiences and from 1944 fought for the liberation of his homeland from totalitarianism with the United States Army. He was an intellectual with two PhDs and, like Kissinger, was conscripted to the army in 1944. He made an impression on the younger Kissinger as they got to know each other as G.I.s at the end of the war.

Kissinger’s own strong sense of idealism becomes clear in several passages such as when, during his time as a counterintelligence officer carrying out denazification, he told his men that we must prove to the Germans by the firmness of our actions, by the justness of our decisions, by the speed of their executions that democracy is indeed a workable solution… Lose no opportunity to prove by word and deed the virility of our ideals.

Fritz Kraemer also saw himself as a missionary of freedom and co-founded the American school of thought Peace through Strength. Henry Kissinger later remembered him as […] the greatest single influence of my formative years. An extraordinary man who will be part of my life as long as I draw breath.

After Kissinger returned to America, like two million other American servicemen, he took advantage of the G.I. Bill and went on a Harvard scholarship, accompanied by his cocker spaniel, Smoky. He received his AB degree summa cum laude in political science from Harvard College in 1950 and his MA and PhD degrees at Harvard University in 1951 and 1954, respectively. His doctoral dissertation was titled Peace, Legitimacy, and the Equilibrium (A Study of the Statesmanship of Castlereagh and Metternich).

Serving as a consultant to the director of the Psychological Strategy Board, his research focused mostly on what could broadly be described as international relations and political strategy. By the late 50s, Kissinger’s academic work at Harvard had plenty of financial backers from the Ford Foundation, the Rockefeller Foundation, the Rockefeller Brothers Fund, over the Dillon family to Standard Oil and IBM as well as the university itself. As a result, he never had to devote much time to fund-raising.

As his work continued to gain influence in Washington, he became gradually more entangled with political figures. In 1960, the Washington Post identified Kissinger as a ‘private adviser to Kennedy on foreign policy’. As a result, any remarks he made in front of the press started to be weighed by officials internationally. When he arrived in Peshwar as the guest of the Government of Pakistan’s Public Information Department, he began his speech at the Pakistan Air Force headquarters with self-depreciation:

“I would like to make clear first of all that I speak to you not in any official capacity but as an irresponsible Harvard professor. In fact, there is a school of thought in the United States which holds the view that once you have identified yourself as a Harvard professor the adjective, irresponsible, is quite unnecessary”.

As Kraemer saw his protégé ascend into higher and higher circles, he warned more than once that the pursuit of power might corrupt him [Kissinger], even if his motive for pursuing it was noble. He said to Kissinger in 1957 that until now, you had to resist only the wholly ordinary temptations of the ambitious, like avarice, and the academic intrigue industry. Now, the trap is in your own character. You are being tempted… with your own deepest principles: to commit yourself with dedication and duty. As Kissinger grew closer to his patron at the time Nelson Rockefeller, Kraemer cautioned him:

“You are beginning to behave in a way that is no longer human and people who admire you are starting to regard you as cool, perhaps even cold. You are in danger of allowing your heart and soul to burn out in your incessant work. You see too many ‘important’ and not enough ‘real’ people.“

At that time, Kissinger became the director of the Rockefeller Brothers Fund Special Studies Project. Assigned topics were:

- U.S. International Objective and Strategy

- U.S. International Security Objectives and Strategy

- Foreign Economic Policy for the Twentieth CEntury

- U.S. Economic and Social Policy

- U.S. Utilization of Human Resources

- U.S. Democratic Process – It’s Challenge and Opportunity

One of the results of this work was the “Rockefeller Report”, released on January 6, 1958. Together with his book Nuclear Weapons and Foreign Policy, the report was hugely influential and shaped the intellectual and political discourse at the time. (Because of his work and German origin, it is a common misconception that Dr. Strangelove was based on Henry Kissinger but producer Stanley Kubrick and actor Peter Sellers have in fact denied this, saying Strangelove was always modeled on Wernher Von Braun.)

Over time, Kissinger became close friends with Nelson Rockefeller. While still governor of New York, Rockefeller planned a White House bid for which he was increasingly seeking Henry Kissinger’s advice. With increasing public and media interest, Kissinger felt the need to clarify his position when he was called a ‘Rockefeller spokesperson’: I am here as a Professor at Harvard and not as a spokesperson for Governor Rockefeller. Governor Rockefeller is a friend of mine and I admire him. When he asks my opinion, I respond to it. This showed to some extent that, although fascinated by it, he was initially cautious about entering the political life. One of Rockefeller’s more Kissingerian quotes to journalists from that time was

Men are moved by ideals and values and not simply by bold calculation. There is nothing automatic about the shape of the future. It is compounded of the vision and the daring and the courage of the present.

Between 1945 and 1969, Kissinger saw Truman, Eisenhower, Kennedy and Johnson as presidents. As a policy advisor, he criticised each of them and ultimately hoped for Nelson Rockefeller, an American aristocrat, to become president as an enlightened ruler. If Kissinger were a true Machiavellian realist, it would be strange that he backed a losing candidate three times. Ferguson shows this as an indication of Kissinger’s idealism but it may also show Kissinger’s naïveté, as he came initially from a position of relative ambivalence about the US. Early on, he noted its unspeakable poverty alongside excessive wealth – And then this individualism!. For a long time, he remained an expert in German affairs but knew less about the country of his citizenship – having visited fewer than 10 of the U.S.’ 50 states by 1959.

In 1964, Rockefeller would run against Barry Goldwater, a radical right-wing Republican. Kissinger was shocked by Goldwater’s rise, a divisive figure, and noted: The frenzy of the cheering […] reminiscent of Nazi times… They [the Goldwater supporters] are the middle class gone rampant […]. They are the result of a generation of liberal debunking, of the smug self-righteousness of so many intellectuals […]. The Goldwater victory is a new phenomenon in American politics – the triumph of the ideological party on the European sense. No one can predict how it will end because there is no precedent for it.

He also wrote:

Every democracy must respect diversity. But it must also know what its purposes are. […] Man cannot live by tired slogans and self-righteous invocations. […] The smug, patronizing condescension with which too many of my colleagues (and probably I as well) have treated those less sophisticated was bound to create an emotional vacuum… If the Goldwater phenomenon passes both parties have an obligation to undertake some profound soul-searching. They should ask themselves why peace and prosperity proved not to be enough; why the middle class became radicalized during a period of material well-being. […]

I couldn’t help but compare the various descriptions of the Goldwater campaign to today’s Trump phenomenon. Even Kissinger’s quote above, which dates to roughly 1960, seems incredibly relevant today. In his first book ‘A World Restored‘, he writes that history teaches by analogy and not identity, which is certainly true in this case but one is still left wondering what recurring stresses and strains American society is under today that are driving a similar kind of populism.

In the 1960s, intellectual circles debated the Non-Proliferation Treaty heavily. The multipolar, post-colonial world had morphed into the bipolarity of the Cold War. This has paradoxically reduced the superpowers’ influence over smaller countries because, logically, each new power that joined the nuclear club would itself substantially reduce the value of membership. Nuclear capabilities as a whole were losing credibility as deterrence is itself tested negatively by things which do not happen even though it is never possible to show why something has not occurred. Perhaps a deterrent wasn’t necessary in the first place. Many saw that, and Kissinger may be included in this, that the longer the ‘long peace’ between the superpowers lasted, the less their citizens understood their debt to the balance of terror.

One fascinating episode in the book is when on October 27, 1962 – a Saturday – the world probably came closest to destruction. That morning, a Soviet SA-2 rocket had shot down an American U-2 over Cuba while another U-2 had unintentionally strayed into Soviet airspace near the Bering Strait. The situation was so tense that mere accidents brought the potential apocalypse even closer: That same day a wandering bear at Duluth Air Force Base led to the mobilising of nuclear-armed F-106s in Minnesota and a New Jersey radar interpreted a routine test at Cape Canaveral as a soviet missile. Vice president Lyndon Johnson was pressing Kennedy for a military response, which would surely have meant all-out nuclear war. US Defense Secretary Robert McNamara remembers stepping outside the White House to savour the livid sunset. To “look and smell it“, as he recalled, “because I thought it would be the last Saturday I would ever see.” At precisely the same time, in Moscow, Fyodor Burlatsky, a senior Kremlin advisor, telephoned his wife to tell her to “drop everything and get out of Moscow.”

Many historians believe that would Johnson have been president, World War III would have ensued. The story continued, that Krushchev was actually asleep on a Kremlin sofa during the episode and only received his ambassador’s report the next morning (incredibly, via Western Union) with a briefing of what Kennedy had said, to which his response came […] in order to save the world, we must retreat. Kissinger later considered this a ‘colossal error’ that made no military sense as it confirmed that the U.S. enjoyed nuclear superiority. He concluded that Whatever one’s reservations about the counterforce strategy […], it proved its efficacy in the Cuban crisis. For this crisis at least, the credibility of our deterrent was greater than theirs. This strategy was, adequately, known as ‘MAD’ for mutually assured destruction.

Sure enough, there’s a fitting scene from Dr. Strangelove in which the Soviets reveal that they have built a doomsday machine as a MAD deterrent:

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2yfXgu37iyI&w=560&h=315]

That same year, Kissinger had been promoted to a full professorship at Harvard but has also continuously written about the Cuban missile crisis and its strategic aspects. He was very much a Kantian idealist in statements such as The insistence on pure morality is in itself the most immoral of postures. Consciously following Clausewitz’ realisation after 1815 that in the future not all wars would be absolute, he argued that limited wars could still be fought and necessary, even in an age of superpowers and thermonuclear weapons. Ferguson is ultimately convincing, however, when he argues that, contrary to the popular view, Kissinger was not simply a pragmatic realist.

The book inevitably leads to the most controversial period of Kissinger’s public engagement – the period of the Vietnam War. It is often asserted that Kissinger was a supporter of the war throughout the 60s and was, indeed, brought into the role of national security adviser under Nixon because of this. The book shows that while he publicly supported Johnson and the necessity to support South Vietnam against ‘Communist aggression’, archival records show that he was a scathing critic in private.

Niall Ferguson goes on throughout this period but it never becomes entirely clear why Kissinger decided to keep such criticism to himself.

Kissinger published an essay in Foreign Affairs called ‘The Viet Nam Negotiations’ around the same time when Nixon invited him to join his administration as national security advisor. When he heard of his appointment he tried to stop the publication as he knew it would be seen as a blueprint for the administration’s policy. While his article was widely perceived as brilliant in its analysis, his wider focus as a member of the administration was beyond Vietnam where he sought to achieve an ‘honorable peace’.

He saw that the U.S. system of formulating and executing national security strategy was a mess and sought to reform it. The Economist wrote at the time that they found in Kissinger’s writing and excellent resistance to the clichés of the day and […] a proper and likeable capacity to admit that he might have been wrong. They continued that he does bring to the new Administration a touch of the intellectual arrogance which it might otherwise be sadly short of.

Although the book ends in 1968, it hints at what the second volume will hopefully deliver. The ‘sorcerer’s apprentice’ as the book calls him, would become the power broker in his new position as Secretary of State under Richard Nixon. Fritz Kraemer’s warnings came as he was already well on his way to become more Bismarckian, whose legacy he has, ironically, studied and described in such detail as an academic.

In September of last year, I was invited to a reception by the Hudson Institute in New York. For dinner, I sat at a table close to Henry Kissinger and when most of the attention turned to the speaker, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, I introduced myself to him with the small anecdote that my grandfather still wore coats and suits with the Kissinger label as Kissinger’s father (I presumed) was my family’s tailor in Nürnberg back in Germany before both our families emigrated to escape the Nazis. Kissinger actually corrected me that this was his uncle and not his father. We briefly discussed the retreat from globalisation as a radically new recent phenomenon. He was very polite as I excused myself with a handshake and that it was an honour to meet him.

Coincidentally, I just started reading his biography at the time and felt that meeting him in old age almost personified the world order he had shaped and which I still grew up in. It is a world order that overall has produced relative peace and immense prosperity – if not without any cost. It ultimately leads us to a paradox, which Kissinger has referred to himself, namely that while modern technology has created a community of peoples, our political concepts and tools are still imprisoned in the nation states. The triumph of self-determination, welcome as it is, has come at the precise moment in world history when the nation-state can no longer exist by itself.

As a dual citizen and with family spread across multiple countries and continents, I have always regarded myself as an internationalist and ultimately a humanist, with no outsized patriotism for one place or another. I wonder how much Kissinger feels the same way and how much his life-long mission was ultimately motivated by a supra-national belief in freedom and ideals over political power play in favour of ‘his’ government or, indeed, whether he saw one as a means to promote the other.

And now for a world government – What has changed since – Kohlmann Notes

July 16, 2017[…] Ambition and that it makes the very concept of nation states somewhat outdated. In my post on Kissinger: 1923-1968: The Idealist by Niall Ferguson I quoted Henry Kissinger: The triumph of self-determination, welcome as it is, has come at the […]

Cities versus Country - Kohlmann Notes

June 8, 2018[…] the age of a ‘new world order’, something I’m referring to in my review of Henry Kissinger’s biography by Niall Ferguson. Most decades since WWII have been dominated by geopolitical hegemony between the Western bloc and […]