With the classical music season 2018/2019 in full swing, I already listened to a lot of wonderful concerts in the last couple of weeks and months. As always when attending live performances, there was more to them than just the music. While a lot of classical music has proven timeless (although even hundred-year-old classics come in and out of fashion), it is always performed in the context of our current times. Where is the music performed – what building and architecture do we find ourselves housed in? Who are the musicians and where are they from? Orchestras have probably never been as international and diverse as they are today. By looking around the performers on stage and reading through the profiles of musicians in the concert program it generally becomes clear that music is a global effort.

While I’ll return to the the politics of our time later on, let’s discuss what’s been on the audible menu so far. Things started off with the York Philharmonic on November 7th – Beethoven and Schubert. Nothing like Schubert’s Symphony No. 5 and of course Beet 4, the underrated sibling of Beethoven’s 3rd and 5th Symphonies, to get into the festive mood. And then there was Schubert’s Der Hirt auf dem Felsen (The Shepherd on the Rock), a lovely piece written just a few weeks before the composer’s death and delivered in an outstanding performance by the New York Philharmonic’s Principal Clarinet Anthony McGill.

The Philharmonic was conducted by Iván Fischer, the Hungarian conductor and composer, which ties neatly back into how music ties into our current lives and political context. While listening to some exquisite Schubert and Beethoven in New York, my mind drifted and I thought about Fischer’s political activism in Hungary. While he is not as radical as his (former) compatriot Sir András Schiff, he nevertheless publicly criticizes Hungary’s increasingly illiberal politics. Fischer’s brother Ádám gave a speech in Brussels in 2011 warning of the rise of anti-Semitism, homophobia and xenophobia in Hungarian society. They both share a similar background with Schiff who was also born in Budapest to a Jewish family and declared in 2012 that he would never again set foot in his country of birth again. He has since also renounced his Austrian passport and became a British citizen.

More than through political vocalism, Iván Fischer himself expressed his background and views as a composer, writing the Spinoza-Vertalingen on a 17th-century Dutch translation of Baruch Spinoza’s text. His most famous piece is probably Eine Deutsch-Jiddische Kantate, which has been performed in Germany, Austria, the Netherlands, Switzerland and the USA. His opera The Red Heifer is written specifically to criticise the growing tolerance for anti-Semitism in modern Hungary. Another reminder of how classical music is interwoven with current times…

_____

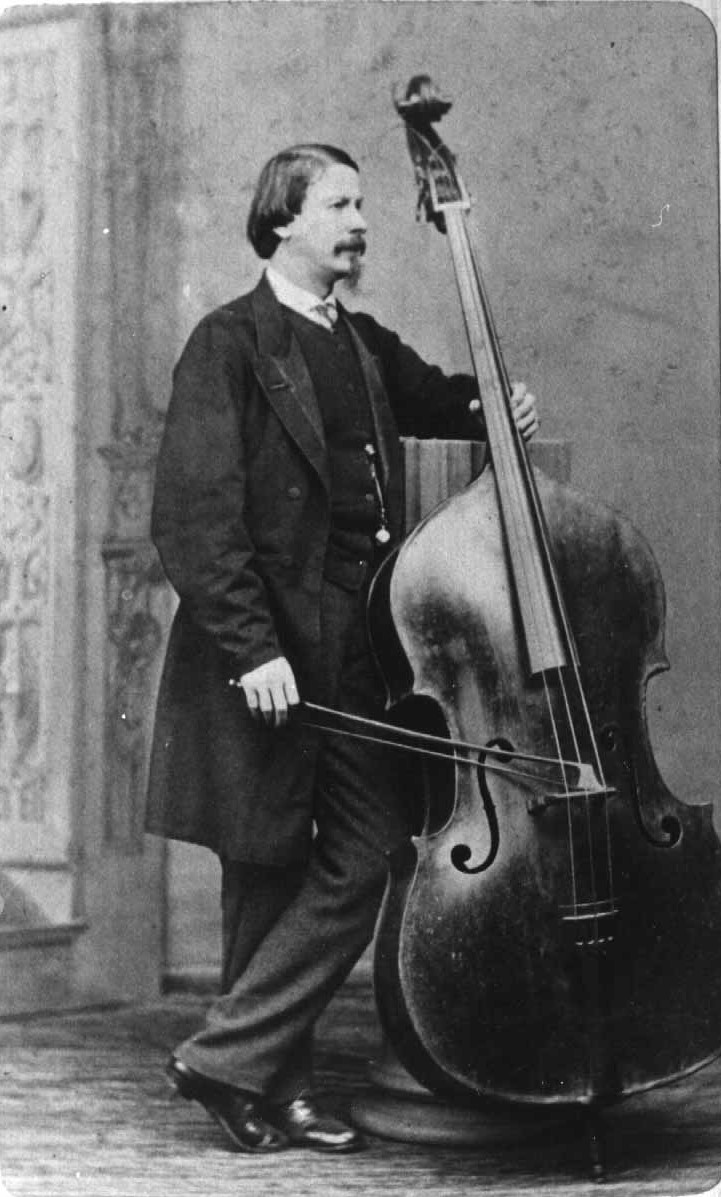

About a week later, on November 13th, New York’s Chamber Music Society performed a lovely variation by Beethoven on Mozart’s famous Bei Männern welche Liebe fühlen from Die Zauberflöte. This was followed by some Schubert (never a bad idea) and an interesting show-piece for double bass by Bottesini (Gran duo concertante for Violin, Double Bass, and Piano, 1880). The latter is technically very demanding and was phenomenally played by Xavier Foley. The Italian romantic composer Giovanni Bottesini is widely acclaimed for his contributions to bass technique and his virtuosic skill, which was said to rival that of Paganini on the violin. So far a pretty impressive show that was finally topped off with Schubert’s famous Trout Quintet (Quintet in A major for Piano, Violin, Viola, Cello, and Double Bass, D. 667, Op. 114, “Trout”, 1819). Not a bad start to the season.

______

The next day came the highlight of the season so far. My family and I recently started supporting the West-Eastern Divan orchestra, which was brought to life in Weimar by Daniel Barenboim and his friend Edward Said in 1999. The orchestra, and now also academy, has since moved to Berlin where they are housed in a beautiful building with the Frank-Gehry-designed Pierre Boulez Saal, which I both went to visit earlier this year. While its mission is often mistaken for wanting to ‘bring peace to the Middle East’, it’s real goals according to Daniel Barenboim are actually much more modest. It simply aims to create a platform for shared humanistic values, for bringing different people together and, maybe most importantly, to create wonderful music together. That alone is an achievement and the political rows that often erupt around its performances are merely validating its raison d’être.

Most remarkably, in less than two decades under Barenboim’s leadership, the orchestra has risen to the highest musical ranks. Although the wind instruments were maybe a little bit weaker than the strings that evening, their concert at Carnegie Hall on November 8th was an exceptional performance, easily rivaling the New York Philharmonic in quality. It was so refreshing to see a young orchestra, playing with such energy and excitement. During the concert one had to remind oneself that the musicians come from backgrounds that would under different circumstances more likely encounter one another in conflict rather than in music. This only underscored the natural and effortless sound of the West-Eastern Divan.

From conversations with its management and musicians, I know that many individuals were only allowed entry to the U.S. because of months of preceding diplomatic efforts that made it possible for those who happen to hold the ‘wrong citizenships’ to bypass America’s ‘muslim ban’. In some cases, ambassadors had to be involved and even appeals to the highest organs of the U.S. government be made for this sound to be emitted that night – once again capturing our current political environment in music. In an age of identity politics and Buzzfeed it was wonderful to meet some of the other supporters over dinner before the concert and learning that there are still others who love classical music and believe in cross-cultural initiatives. Seated at my table was actor Alec Baldwin who also assured me that he would much rather forget about his role as a political impersonator over the past two years.

Following a lovely programme of Strauss (Don Quixote), Tchaikovsky (Symphony No. 5) and a first encore, Daniel Barenboim did something special, which made headlines around the world about 17 years ago. Never shying away from controversy, in 2001 Barenboim famously played a piece from Richard Wagner’s Tristan and Isolde as a second encore at a concert in Israel after another piece by the composer was dropped from the original programme following protests. It was followed by a 30 minute debate among the audience and provoked an outcry among Israeli society with a vocal political debate that ensued. Although somewhat less controversial in New York, he pulled off his signature move again by playing the prelude of Wagner’s Die Meistersinger as a second encore to continued thundering applause.

Overall, this performance was an example of what is possible through international collaboration. With this in mind, it is also incredibly sad that the world is diverging from this path towards a more nationalist future. In Donald Trump’s words: “You know what I am? I’m a nationalist. OK? I’m a nationalist.” With such political thinking on the rise, we can expect to be seeing less and less of this kind of collaboration in politics, science and also the arts. Despite its timeless aspects, classical music will probably be equally affected. The West-Eastern Divan is working against this. I’m proud to be supporting this cause and wish them every success.