It was a true privilege having been invited to the premiere of Lulu at the MET Opera in New York by a dear family friend. As someone who is very interested in works by the incredibly productive and innovative pre-war German writers and artists, I was particularly curious about Alban Berg’s Lulu. This was the first time I saw his opera and expected an amalgamation of Arnold Schoenberg’s music, Karl Kraus’ gallows humour and dark Kafkaesque confusion. This proved more or less right. The piece reflects a deep, visceral discomfort felt by a changing society – a society yearning for modernity but stuck in an old-fashioned world view, struggling to free themselves from the shackles of the previous generation’s dogmas. This cultural angst and search for one’s place and sense of purpose in a cosmopolitan society was also what marked the works of many other creative minds of the period. Before the beginning of the performance, I debated with a friend whether we might have reached a similar point again today.

After two generations of fighting for capitalism, democracy and political integration in an ever-ballooning economy – a fight that is essentially won – large parts of society feel alienated by continuing globalisation, political acceptance of fully liberal values and a decline in religious beliefs. This hasn’t really lead to any form of widespread backlash yet – nor is it inevitable – but it is all too easy for our countries’ elites to forget that many in their societies have evidently not profited as much from globalisation and are therefore not automatically enchanted by the idea of an ever-more global and cosmopolitan world. It is also easy to forget that this appreciation requires hard work to be nurtured and without the privileged education one might have enjoyed, it is far harder to have the interest and open-mindedness to accept other peoples and cultures closer to one’s own life. At the ‘outbreak’ of fascism in Europe, large swathes of the German cultural elite were naturally appalled but also truly shocked about how their fellow countrymen could welcome such vile ideologues. They, too, underestimated what has been simmering under the surface for a long time. Art, for example, progressed at a breathtaking pace to the rightful admiration and cheers of leading collectors and intellectuals. As artists freed themselves from the shackles of past dogmas and broke taboos, they elevated their field to unprecedented heights but also alienated many people – something that was largely ignored or misunderstood. The Nazis famously put a collection of so-called ‘degenerate art’ on display in Munich, every single piece of which has later become a cultural treasure – works of genius ahead of their time. In Lulu, this uncertainty and discomfort can be felt when, for example, every time someone knocks on the front door of an indoors scene, all characters let out a scared sigh and quickly go into hiding, worried about what drama might enter this time.

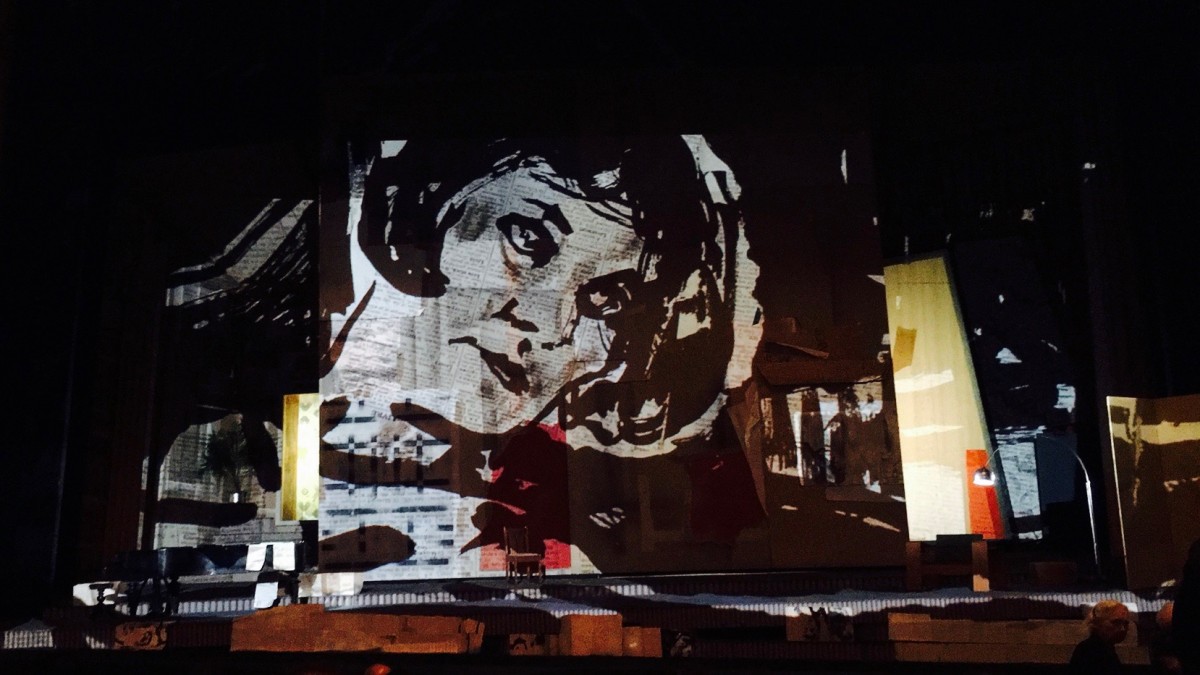

A revolution in Paris? The police? No one seems to be able to make sense of these chaotic times. The opera comes to life through William Kentridge’s wonderfully crafted projections, which further remind the audience of the time of Berg with their look typical for the 20s and 30s. Another remarkable element of this Opera is its music. Alban Berg built Lulu’s score on an elaborate technique with rows of twelve notes encapsulating situations and feelings. This is, of course, very much Arnold Schoenberg, who taught Berg. Schoenberg’s compositional system replaces the traditional theory of harmony from the Classical and Romantic era with an entirely new structure. Here, all twelve notes within an octave are treated equally. This is what makes Schoenberg’s music so unique and innovative and Lulu the first opera to implement its principles. The music is therefore another element that transports the audience firmly into the 20s and 30s.

Defending ‘atonal music’ in this interview with Radio Vienna in 1930, Berg states the following:

Even if a few harmonic resources are lost along with major and minor, all of the other prerequisites of “serious” music are preserved.

It is important to remember that only the first two parts were in fact finished by Alban Berg, whereas the third was added much later to finish a complex incomplete work. Ultimately, however, it seemed as if the academic heft and gloominess of Lulu was too much for many in the audience to bear, as the ranks have emptied significantly after each of the two intervals of this (admittedly) overly long opera. Lulu‘s historic significance, cultural relevance and superb delivery by William Kentridge is nonetheless unquestionable.

Kaz

November 12, 2015Great review! Really enjoyed reading. You and your bro have a similar writing style.